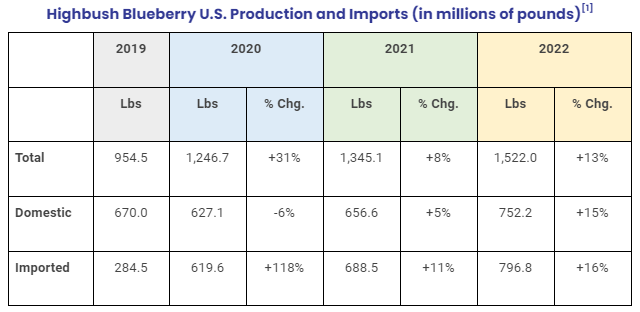

As the ancestral home of blueberries, the USA has witnessed phenomenal production and import growth in recent

years, to the point where - if forecasts materialize - the total volume in the market in 2022 will be up

almost 60% on 2019 figures, which were already at a high base. Imports overtook domestic production in 2021,

driven primarily by growth from suppliers in Peru and Mexico followed by Canada and Chile.

Rising imports have been a source of friction in the U.S. industry, particularly for growers whose market

windows overlap somewhat with Mexico in the spring months, Canada during the summer, or Peru in the fall. A

latter portion of Mexican supply coincides with Florida and impacts what was previously the “early season

windows” for California, Georgia, North Carolina and elsewhere. Meanwhile, growers in the Pacific Northwest

and Michigan are also seeing their late season fruit in MA and CA storage competing with Peru in addition to

the ongoing summer overlap with British Colombia.

This competitive environment has triggered consolidation in the industry as well as financial stress for

some, but also increased productivity and innovation for the industry at large to lift yields, reduce

harvesting costs with the help of machines (a practice that now represents the majority of volume in several

states), and renewed efforts to produce varieties that deliver a better eating experience for consumers.

As one U.S. grower stated in response to the heightened competition: “Sometimes the worst of things brings

out the better things. We need a little kick to get us off the old varieties.”

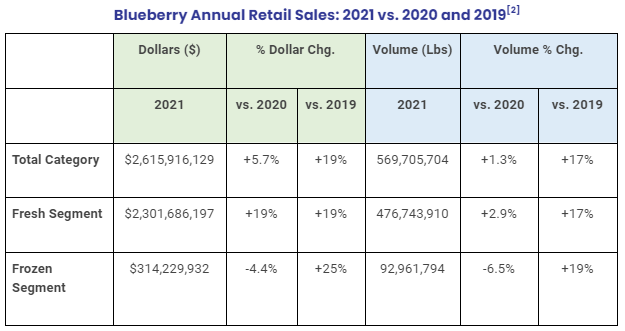

The market absorption of such a large influx of volume, in a way that is economically viable, would not have

been possible without a meaningful boost to demand. The tireless efforts of the U.S. Highbush Blueberry

Council (USHBC) to fund health research paid dividends during the pandemic both at home and globally thanks

to positive associations between blueberries and high levels of antioxidants, among other health benefits.

As referenced in the 2021 State of the Industry Report, the North American Blueberry Council (NABC) launched

pilot programs during the pandemic to utilize digital technology to build demand, and many of these

initiatives have since become always-on components of the commission’s market strategy. Alongside marketing

techniques that harness social media, e-commerce and geotargeting, one example highlighted by the NABC is

digital video advertising on streaming platforms like Hulu, creating “one-to-one pull-through” whereby

commercial success can be measured by purchases resulting from clicks.

When the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) ruled in early 2021 that imported volumes were not causing

serious injury to American growers, it was a disappointment for those who had initiated a Section 201 global

safeguard investigation. The episode was also a wake-up call to marketers and importers about the need to

invest further in market development. One of the great positives to come out of that was a trade taskforce

spearheaded by the NABC that was able to bring both sides of the conflict together to work on solutions and

new marketing funding mechanisms. By December, companies accounting for half of the USA’s blueberry imports

in dollar terms had signed on to increase voluntary financial contributions. The scheme originally applied

to importers of record, but has since expanded to exporters and is set to galvanize the NABC’s capabilities

in marketing, business intelligence and building price reporting systems.

The price reporting mechanism in its current iteration will not be able to achieve the “gold standard” of

California where it is state mandated, but the NABC is drawing inspiration from the avocado industry to

bring useful, transparent information under a centralized data house. This is very much in alignment with

what the International Blueberry Organization (IBO) hopes to achieve on a global level with industry

improvement through data transparency.

Production Trends and weather impacts

Inclement weather and labor availability are two predominant themes across the U.S. blueberry industry,

presenting challenges that have held back crop volume growth from its true potential. Industry leaders often

quip about how volume would look if every state experienced the perfect conditions, but for now that

eventuality is unlikely as climate change is leading to a greater frequency and intensity of extreme weather

worldwide.

It seems that every year at least one major region is beset by a major weather event. Last year it was

hailstorms in North Carolina and an atypical heat dome in the Pacific Northwest, where in late 2021 there

were also floods in both Washington State and across the Canadian border in British Columbia; the long-term

effects of which are yet to be felt but will be diluted in the numbers due to the scale of plantings yet to

reach maturity with higher-yielding varieties in WA.

The effect of volume growth in the pipeline due to younger plantings was so great in WA that there were even

cases of farms with up to 15% of the crop damaged from heat, but still registering record total harvests.

One industry representative expects volume from the state – already the largest producer in the country -

could in the next few years plateau at around 250 million pounds (~113 million metric tons), which would

represent a rise of almost a third on current annual volume.

Oregon would have had a record crop last year had it not been for the heat dome, marking a second consecutive

year when yields were off because of weather. Compared to Washington State, Oregon has a much higher

percentage of fruit sent to the fresh market, but the hot weather did impact quality and meant a greater

proportion of berries was sent to processing than usual. Less than 10% of plantings have some kind of

evaporative cooling system in place to mitigate damage. The industry’s irrigation capacity is highly

dependent on snowpack in the Cascade Mountains, which is fine at the moment but as is the case in all

blueberry-growing areas with glacial or snowpack dependency, concerns remain for a warmer future and what

impact that might have. Unlike its neighbor to the north, and to a lesser extent to the south in California,

new planting has slowed somewhat in Oregon.

This year (in 2022) Georgia and parts of Florida had to deal with spring freeze events, which in Georgia’s

case drove significant year-on-year weekly volume declines (ranging from 20-81% depending on locale)

throughout the first few weeks of May. Whereas in the past those growers who had supply could compensate for

volume declines with better pricing, that possibility has been strained by increased competition from Mexico

and competing domestic regions (in this case California) which was consistently shipping more fresh

blueberries into the U.S. market year-on-year throughout March, April and May. In the first week of May, for

example, USDA shipping point prices for Georgia-grown and Florida-grown blueberries were down 39% and 37%

respectively.

Growers in the USA’s oldest commercial blueberry-growing states such as New Jersey, Michigan and North

Carolina – three of the largest producers outside of the West Coast – are also feeling the effects of

climate change.

Michigan has been dealing with unusually cold springs in recent years and has been affected by rain and frost

events. One grower in the state, where the typical farm is much smaller than on the West Coast, said they

needed to use frost protection for 11 days out of a two-week period in May 2021 with wind machines and

overhead irrigation. Despite all that work, and expenditure, there was a high level of rainfall just before

the start of the harvest season in the second half of June. This affected the variety Bluecrop, which

accounts for an estimated 25% of plantings in Michigan, very badly. As a result, Michigan too had to send a

greater proportion of fruit to the processed market.

New Jersey, whose season has traditionally been tied to the peak 4th July sales period in the most populous

part of the country, is increasingly dealing with rains during the harvest period which didn’t used to

happen. A tropical storm experienced in the middle of the season in 2021 wasn’t as bad as in 2020, and the

crop wasn’t as low as it could have been considering a warm streak of weather during the flowering period,

making pollination more of a challenge.

Like Oregon, North Carolina would have seen a record crop in 2021 if it weren’t for a weather event – in this

case a hailstorm. The state’s growers have also been dealing with unseasonably mild spells in winter that

have put certain cultivars at risk, prompting early blooms that put the bushes at greater risk from freezes.

Another challenge is that overhead irrigation doesn’t work for wind-borne freezes that are common in the

state.

As referenced in the Industry Trends section of this report, inflationary pressures (including fertilizer,

gas, packaging, crop protection) have been a major headache for the blueberry industry as they have been for

most sectors of the economy, and the U.S. is no different. What this has done, however, is accentuate the

comparative advantages of growers that are close to their target markets, often tilting the cost-benefit

equation in favor of ‘local’ or ‘regional’ supply, for example New Jersey blueberries in the Northeast, or

even smaller blueberry industries such as Mississippi and Louisiana for the Delta area.

Labor scarcity and adaptation

Despite being hit by freeze events in coastal areas last season, the Californian industry was still able to

pick its largest crop on record in 2021, and volume could have been even larger if it weren’t for a lack of

labor availability.

It has been an industry-wide problem for a while in the USA and elsewhere, but labor scarcity issues have

become exacerbated since the pandemic began. Farms that need blueberry pickers through the H-2A temporary

worker visa program are needing to get creative to make their operations more attractive to workers who

could just as easily go to other sectors such as construction. From the West Coast to Florida, some have

built or are building their own lodgings to make themselves more attractive to either pickers or

contractors, while legislation has been lifting minimum wages in numerous states and this year Oregon

introduced a law to transition into a 40-hour workweek limit by 2027.

For a large part of the industry, overcoming the labor challenge means adapting to machine harvesting for the

fresh market. If successful, and if a grower can afford the capital cost of the machine or machines, renting

one, or sharing it across several farms, their cost base can be reduced. However, the cost-benefit analysis

is often framed as a matter of necessity. As one grower-marketer stated, “The elephant in the room is

whether you want to get the fruit off or you don’t.”

As the blueberry industry climbs up the steep learning curve of machine harvesting for fresh, the impact of

the practice on yield varies greatly, as does the choice of variety and orchard structure. As it stands

currently it is almost guaranteed that a portion of machine harvested blueberries will be wasted due to

fruit damage, as well as the fact the harvesters will take off berries that are unripe and would otherwise

have been handpicked later.

Plants need to be trellised and pruned such that the structure stays upright and machines can gently detach

berries as they’re moving through the row, and northern highbush varieties have a comparative advantage over

southern highbush in that they tend to require fewer runs in the rows throughout the season due to harvest

concentration. The other advantage lies in the fact the Pacific Northwest growers have been doing machine

harvesting for fresh for longer than elsewhere, and have worked on techniques with established commercial

varieties that are, according to grower contributors to this report, more conducive, such as Duke, Blue

Ribbon, Draper, Calypso, Top Shelf, Envoy, and Titanium, as well as hybrids like Legacy.

That said, machine harvesting is now a common practice in southern highbush areas such as Georgia, Florida

and California, although for the latter around 44% of the fresh crop is organic and most of the organic

fruit is handpicked. Some Southern highbush cultivars are demonstrating machine-harvest potential include

Meadowlark, Suziblue and Optimus, but many leading breeders worldwide are focusing on up-and-coming

varieties in this space that are yet to be named. Some producers, marketers and breeders however are

skeptical about the quality assurance (QA) implications of this trend.

It is worth clarifying here that machine harvesting is certainly not the primary objective within the

varietal transformation that is underway in all regions, which is elaborated upon in greater detail within

the Industry Trends section of this report. There are other considerations that shift the yield side of the

equation to improve the return per acre, adjust the harvest timing towards certain windows or expected

weather conditions, or focus on organoleptic, textural and sizing characteristics aimed at enticing

consumers with delightful berries in a way that encourages repeat purchases.

The United States is home to some of the world’s leading private and university plant breeding programs,

yielding varieties that are lifting the benchmark of what consumers are coming to expect in terms of

blueberry quality. Breeders from around the world from Spain to Australia are also busy rolling out new

cultivars with U.S. producers.

Machine harvesting and varietal conversion are two ways growers are adapting to the current environment, but

another is adoption of organics. The U.S. organic blueberry category has grown substantially in recent

years, both on virgin soil and with growers willing to wait the three years it takes to convert a

conventional orchard to an organic one. The premium potential has led to plantings even in very challenging

organic cultivation environments in the Southeast, but much of the organic growth has taken place in drier

areas such as California, Michigan and in Washington State to the east of the Cascade Mountains.

The organic program has skyrocketed in California and, aided by high-density substrate plantings, has the

nation’s highest percentage of organic acreage for blueberries, getting close to 50 per cent of the state’s

fresh crop. This is partly as a response to market opportunities, but is also a reaction to government

policies that encourage less use of pesticides.

Except for a couple of players, most organic blueberry farmers are relatively small and sell to larger

marketers or distributors who sell both organic and conventional. These marketers are usually bullish about

organics and have been encouraging more growers to make the switch, although they can be met with

trepidation because of the perceived high-risk profile of the category that has lost its premium at certain

times of the season, leading some organic fruit to be sold as conventional. Agronomically and in terms of

field-to-packhouse times, organics are more demanding if growers are to achieve yields that make the venture

economically feasible.

As much as many consumers express preference for organics and there is a small cohort of ‘hardcore’ organic

fruit buyers, there are sales channel limitations as less than a handful of national retailers are genuinely

committed to organic blueberries when it comes rotating significant volume at premiums. The fact that

marketers sell both organic and conventional, regardless of their best intentions, also has an inherent

incentive toward moving the most blueberries possible rather than necessarily hitting the highest of

premiums that buyers may be willing to pay if pressed harder.

Export Development

Despite strong domestic demand and supply chain challenges, U.S. blueberry exports increased slightly in 2021

as growers started to consolidate gains made in Asia. Canada is by far the leading export market for U.S.

blueberries, and the same is true vice versa, but this is a mature trading relationship as the two markets

are intertwined. Including Canada, exports represented 16.6% of the U.S. blueberry crop last year but

shipments outside North America have tended to hover around the 4% mark split 50-50 between fresh and

frozen.

Cognizant of the fact that exports can take the pressure of a booming domestic market, the U.S. industry is

well aware of the imperative to lift exports but this also requires a high degree of caution to ensure

quality standards are met. Unlike sectors in South America and Southern Africa that have been developed

around long shipping times, U.S. blueberry farmers have had the relative luxury of proximity to their core

market with the longest haul being a trans-continental truck drive. Shipping across the Pacific Ocean is a

different undertaking, and mistakes can be costly for reputations.

Select growers and particularly vertically integrated grower/packer/shippers have long been building

relationships with overseas importers, but for most, export development is still on the to-do list. This is

the case even for some major players that are experienced in facilitating moving of blueberries from Peru or

Chile into Asian markets, and therefore have the expertise to execute successful programs if they are able

to align their learnings with U.S. growers.

For fresh blueberries, the USA’s leading export markets ex-Canada are South Korea (where only Oregon has

access), Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore and Vietnam, the latter being arguably the greatest export

success story of recent years where exports have been able to plug into the online and social media

ecosystems of one of Vietnam’s leading retail chains, Vinmart.

The USHBC - in conjunction with federal grants and state-backed programs from California, Oregon and

Washington State - has expanded its Southeast Asia program to include Malaysia (a non-protocol market),

Vietnam, and the Philippines (access gained in 2020). This program is not only limited to fresh, but also

includes frozen and dried blueberries.

The Philippines is still an early-stage work in progress where efforts are needed to raise awareness about

the fruit and its health benefits. Retailers tend to prefer small test shipments, which can be discouraging

from a cost perspective for U.S. packers.

Airfreight continues to be the dominant supply route for fresh blueberry exports out of the U.S., and part

of last year’s success can be attributed to major exporters locking in air cargo space early. The

Californian industry had been upbeat about having the use of sulfur dioxide pads approved to extend shelf

life, but port congestion and competition for container space impeded development of this export

channel.

In 2020 market access was gained in China for the U.S. industry, although only West Coast growers are able

to do so without fumigating the fruit. The combination of high tariffs and supply chain problems have meant

little progress has been made on capitalizing on this opportunity to date, not to mention the fact the

Pacific Northwest partially overlaps with a period of large domestic blueberry volumes in China.

It is worth noting some of the regions that have been hit the hardest by imports in the U.S. – such as

Florida, Georgia and California – harvest during periods of relative scarcity in Asia more broadly. In terms

of improving Chinese market access, Florida was one of three states (also Michigan and New Jersey) where

data has been collected on a systems approach without methyl bromide to treat blueberry maggot, but this is

yet to go through the review process with Chinese phytosanitary authorities.

Blueberry maggot and spotted wing drosophila (SWD) are the pests of concern in current market access

negotiations with South Africa, Australia, New Zealand and Israel, with studies involving Michigan State

University and the USDA now completed and awaiting review from APHIS before incorporation into these

international discussions.

Other key priorities for the U.S. blueberry industry minimum residue limited (MRL) harmonization, targeted

health messaging, and altering perceptions of blueberries as an ‘indulgent dessert’ to the snacking status

it has in developed markets, in addition to developing more global markets for frozen and dried blueberries.

The latter will be critical for finding a home for blueberries that may not make the grade in future due to

either machine harvesting damage or changed varietal/characteristic-based preferences from retailers. In

this regard, the NABC and USHBC see a “huge runway” for fruit to find its way into the ingredients channel,

with industry aiming to lift this portfolio through its Global Food Manufacturing Program.

The top export markets ex-Canada for frozen exports last year were South Korea, Japan, Australia, New Zealand

and China, while for dried (the only blueberry category that didn’t see an export rise in 2021) the Middle

East was the main destination, followed by India.