[[ page_title ]]

Global Production Forecast

The production forecast built from the planting and production data projects the global industry volume crossing the 3,000 (000) MT milestone by 2025. This milestone will be driven by continued growth from the Americas, followed by Asia/Pacific* and then the EMEA region, the latter running about two years behind the Asia-Pacific with a similar rate of growth. The report team, however, feels that there is a probable downward trend in this forecast as there are real limitations to production and planting increases including access to land, water and labor, particularly in Latin America that put a constraint on growth which our model is not setup to capture. Additionally, it is the opinion of the report team that over the next couple of years the industry will begin to transition from high growth to a more mature stage, which will clearly have an effect on long term projections.

This year’s projections offer an important improvement in the technology used to create the predictions. By employing Machine Learning, our methodology identified the amount of history used by regressions that offers the least amount of error for each producing region in the dataset.

To add context to the projection, the charts present a scenario (solid line under the forecast) where the growth observed is coming exclusively from hectares planted in 2021 and coming into commercial operation within the next four years. This means that no additional plantings, or increases in yields are used in the forecasts offering the lowest realistic scenario for production, which we labeled as base in the charts. That said, knowing that plantings continue to go in the ground makes the zero growth scenario impossible, but it offers perspective allowing the likely future growth for the industry to lie somewhere between the forecast and the Zero Growth Scenario.

See Production Forecast Methodology at the end of the report for more information.

Americas Production Forecast

The Americas are the world’s powerhouse of production. By 2025 - 2025/26, the forecast created from our historical regression projects the region’s production to 1.6 billion kilos. This number needs to be taken cautiously as explained earlier.

After all the turmoil of the pandemic in 2020, 2021 has broken records for production seeing increased growth for every subregion. In South America the main driver of production continues to be Peru seeing even levels of growth in both hectares and yields. A considerable increase in plantings is expected to come on-line in Chile after 2023, adding significantly to production in the region if uncompetitive fields likely to be removed are not taken into consideration. North America’s production is also expected to continue to grow led by the Western US producers, although most other origins are expected to remain stable. Mexico/Central America, led by Mexico, is growing at a faster rate than South America, albeit from a much lower base. As both South America and Mexico/Central America regions come into maturity, the growth rate is expected to slow down and begin to stabilize, this is partially reflected in the forecast although, as previously mentioned the report team feels that these projections are likely high.

Asia/Pacific Production Forecast

The proverbial elephant in the room is Asia, predominantly led by China. There are a large number of hectares that are expected to come on-line in the next four years driving these numbers.

Echoing last year’s report and as outlined elsewhere in the document, it would be reasonable for a reader to suppose that the data available for China is likely higher than what may actually be produced*. Unfortunately the true values for Chinese production are simply not knowable today. To offer this information in a relevant context as best we can, the report team assumes that the real growth rate of plantings in hectares is 6% while, for the purposes of this forecast the yields have been maintained at their 2021 levels.

Importantly, growth in China is expected to continue. As of yet, Chinese blueberries have mostly been directed at internal consumers, however we are beginning to see limited exports in our datasets to regional partners like Singapore. As the country continues to grow, we may find Chinese blueberries with an increased role on the world stage.

*For more information see the Missing or Anomalous Production Data section in About the Data section.

EMEA Production Forecast

EMEA is expected to see a healthy growth rate bringing its production to nearly 650 (000) MT by 2025. Through the better part of the 2000’s the star player has been Southern Europe and North Africa, however, given the large number of hectares not in production that are expected to come on-line in the next four years, Eastern Europe is being projected to overtake these regions by 2025. Another origin to watch will be Africa which is seeing an impressive growth rate with production having matched Western/Central Europe this year, despite several production issues in South Africa, the continent’s leading producer.

Forecast Error

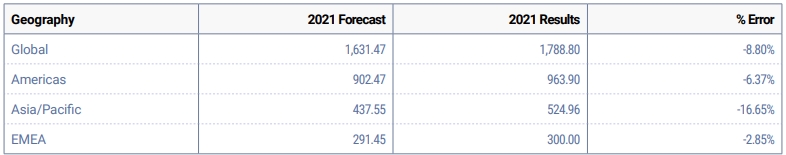

Offering context is crucial to the credibility of any forecast. In the table below we offer the values predicted last year for the 2021 season compared to the actual data collected.

Generally speaking the results of the forecast were quite good, only presenting an 8.8% variance compared to the actual numbers for 2021. The largest error came from Asia, which is mostly due to the lack of reliable data from China. The EMEA error was the lowest at 2.9% thanks to a particularly good forecast of So. Europe/No. Africa, while the Americas was a bit higher than EMEA at 6.37% despite a very low error rate for the US and Canada with higher rates for South America and Mexico/Central America.

Of note is that the error for each producing region is negative, meaning that our methodology consistently under-forecasted actual production. Part of this is due to the production numbers in 2020, which were lower than they could be because of COVID 19 and a myriad of related reasons. The forecasts created with these lower volumes hence produced lower forecasts. As the industry got back up to speed, regions out performed the prediction creating the observed error. Although this isn’t the only reason our forecast was likely to be off, the observation is part of the reasoning behind the emphasis being put on the improvements in the forecast methodology.

For a disaggregation of the forecast error by subregion please visit the Production Forecast Methodology section.

| [[ top10_tables.hectaresByCountry.title ]] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Country | 2018 Hectares | 2019 Hectares | 2020 Hectares | 2021 Hectares |

| [[ top10_tables.productionByCountry.title ]] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Country | 2018 Production | 2019 Production | 2020 Production | 2021 Production |

| [[ top10_tables.freshProductionByCountry.title ]] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Country | 2018 Fresh Production | 2019 Fresh Production | 2020 Fresh Production | 2021 Fresh Production |

| [[ top10_tables.processedProductionByCountry.title ]] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Country | 2018 Processed Production | 2019 Processed Production | 2020 Processed Production | 2021 Processed Production |

| [[ top10_tables.yieldByCountry.title ]] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Country | 2018 Yield | 2019 Yield | 2020 Yield | 2021 Yield |

(Denominated in Hectares and Thousands of Metric Tons)

| [[ tables.region_hectares_table.title ]] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [[ page_title ]] | Planting | 2021 Production | ||||||

| Growth Totals | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Fresh | Process | Total |

| [[ tables.region_production_table.title ]] [[ tables.region_production_table.subtitle ]] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [[ page_title ]] | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||||||

| Productions Totals | Fresh | Process | Total | Fresh | Process | Total | Fresh | Process | Total |

| [[ tables.production_metrics.title ]] | |

|---|---|

¹ Growth in volume produced compared to previous season

² Volume increase from new hectares coming into production

³ Volume increase from higher yields

Global Highbush Fresh

Report Team Narrative

While Fresh Highbush figures are extensively covered in the different subregions and individual country sections. This space gives us the opportunity to explore general global trends not otherwise covered in the report.

Based on the data collected for the 2021 report the production of fresh blueberries rose by 21% breaking the 1,000 (000) MT mark for the first time in history.

Interestingly we see that every subregion saw an increase in production compared to the previous year. This indicator speaks to the increasing relevance of the blueberry category within fresh produce isles the world over. Further illustrating the continued vitality of the industry, North America, the native home of highbush blueberries, and one of the most established growing regions, continues to see strong growth adding 26 (000) MT over the last season, mostly from increases in yield, which points to replantings with new varieties and updated growing systems in core growing areas.

China and Peru stand out as the countries adding the most volume of fresh blueberries. The Peruvian data is provided from industry sources highly engaged with growing and exporting companies in the sector (the Industry Guild). The Chinese data sources are less concrete and we acknowledge the possibility that the actual hectares and production figures may indeed be lower. All the while there are exciting newer growing regions in Africa and India looking to bring blueberries to new consumers in the years to come.

Blueberries are one of the most exciting and fastest growing produce categories. Thousands of people in this industry steadily work year after year to paint the map of the blueberry world. Many thanks to all the contributors to the data presented in this report, your continued support helps serve a more informed industry seeking to develop a sustainable industry for producers and ever better experience and access to consumers.

| [[ tables.region_production_table.title ]] [[ tables.region_production_table.subtitle ]] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [[ page_title ]] | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||||||

| Productions Totals | Fresh | Process | Total | Fresh | Process | Total | Fresh | Process | Total |

Global Wild Production

Report Team Narrative

Wild blueberries have seen a rebound in pricing worldwide since the pandemic began, prompting the reactivation of blueberry barrens in Maine that had been left temporarily fallow following the impacts of oversupply problems in 2016. However, other contributing factors to the steady production decline in the state in the years preceding the pandemic have not gone away – pest and disease pressure, volatile climatic conditions, aging wild blueberry farmers with succession challenges, and the opportunity costs of holding coastal land where these berries are picked that in some cases is being converted to wind and solar farms.

Maine and eastern Canada account for the largest share of global wild blueberry production with the native Vaccinium angustifolium as the main species representing 95% of North America’s crop while the remaining 5% is Vaccinium myrtilloides, also known as the velvet leaf blueberry. Because of the difficulty transporting wild blueberries fresh in marketable condition, 99% of the fruit is frozen with the berries put in the freezer within 24 hours of harvest and stored for up to three years.

A variable climate with a combination of frosts, freezes, drought and higher temperatures has negatively impacted the productivity of wild blueberry fields, which in the lead-up to the 2016 peak season were in a state of expansion in Canada and overall decline in Maine. In 1995 both Maine and Canada had equivalent levels of wild blueberry production, but the Canadian Government released tracts of Crown land to private growers and encouraged growth in the Canadian sector which now produces a much larger volume than the U.S. North America’s 2021 wild crop would have been significantly larger if it weren’t for weather- and drought-related conditions experienced in Quebec.

With an industry spread across different Canadian provinces plus one principal U.S. state, there is a degree of diversification at play with wild blueberries picked – predominantly by machine – in areas with very different conditions, which somewhat, but far from entirely, offsets production volatility. For example, in 2020 Quebec produced by far the largest volume in the continent, but in 2021 it was well behind Maine, and grew less than New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Prince Edward Island is another production region of note, while Newfoundland has miniscule volumes.

Quebec has a continental climate unlike other Canadian wild blueberry growing provinces with more maritime climate conditions, and the province suffered a crop failure in 2021 prompted by drought and spring frosts, setting it back below levels it had been tracking at for more than a decade. It is worth highlighting Quebec still has opportunity to grow, and the number of acres where wild blueberries have been activated has approximately tripled within two decades. In New Brunswick there is a new strategic plan to release more Crown land, which if implemented would unlock a 69% increase in land for the crop by 2035. Meanwhile, in Nova Scotia some less productive land is due to be taken out of production, but the industry projects it can double output by increasing production inputs. A major limiting factor in Canada will be the availability of pollinators as the native overwintering hives are not strong and the hives produced from Ontario are variable. Maine, in contrast, can source strong, active hives from the southern US and so does not have this limitation.

The fruit is grown in naturally occurring wild stands in the northeast of North America that evolved after glacial retreat 10,000 years ago, and based on observations of the average plant cover, experts estimate an average of 270 different genotypes can be found per hectare. Growers believe it is this diversity that gives the fruit its unique character. Wild blueberries are also smaller than highbush blueberries, and the wild blueberry industry’s proponents claim they also have more antioxidants. The wild blueberry industry continues to invest heavily in lowbush blueberry-specific health research and promotions.

In an environment where demand is currently exceeding supply, the Maine industry has a large domestic focus in addition to Canada-oriented exports, but the state also exports to Japan, South Korea and the EU with overseas shipments aimed at preserving customer bases. Canada exports about half its wild crop to the U.S., in addition to others such as Germany, Japan and China.

Wild production outside of North America is difficult to track and is based on best estimates from industry sources.

In terms of European wild blueberry production, Vaccinium myrtillus or the European bilberry is native to the continent as well as the Caucuses and much of Asia. Scandinavia is a major source of production with bilberry bushes to be found throughout the forests of Norway and Sweden, although only the latter has a sizable commercial industry. However, crops are extremely variable as is access to labor with pickers needing to be flown into the harvest regions in many cases. It is also highly likely, but not corroborated, that the conflict in Ukraine has disrupted wild blueberry harvests in Eastern Europe.

Chinese Wild blueberries

‘Chinese Wild’: Vaccinium Uliginosum L. and Vaccinium Vitis Idaea are native to China, particularly the forested northern provinces of the country. The native Vaccinium Uliginosum is often dark reddish-blue, red or dark blue and often referred to as “蓝莓”(pronounced “Lan Mei”). “Lan Mei” is the most common word used for blueberries in China and now applies to highbush as well. Meanwhile the Vaccinium Vitis Idaea, or Lingonberries, are a deep red and also native to the northern reaches of Europe, especially Scandinavia. These berries are harvested most often by villagers who live near the forested areas where these species grow. The fruit is then sold on to brokers who process the fruit or resell it to processors who sell the finished product. Most of the fruit is now sold domestically, often as a health product in teas, powders, dried fruit, extracts and even cosmetics. Annual production is largely contingent on the amount harvested from the wild and the impact of winter weather on the crop.

‘Chinese Cultivated Lowbush’: Another interesting segment of Chinese domestic blueberry production is the ‘Cultivated Lowbush’ industry. In the far northern provinces of Jilin, Heilongjiang and the continental north of Liaoning, the extreme winters have proven a challenge for traditional highbush production. Early trials conducted in the late 1990s and early 2000’s led by Jilin Agricultural University, showed that the cold hardy Lowbush and ‘Half High’ cultivars were more likely to crop and survive in the harsh conditions. Most of these varieties are considered ornamentals in the rest of the world while a few others represent exemplary selections from Wild patches in North America sourced from the USDA germplasm repository in the 1990’s. Cold hardiness, increased likelihood of protection from snow cover (due to plant height) and apparent tolerance of difficult soil and moisture conditions have led to the large-scale planting of Cultivated Lowbush (in rows) and ‘Half High’ blueberries. Due to mixed information available from China, it is likely that most of the ‘cultivated lowbush’ production from China is represented in the Highbush production and acreage figures for China.

| [[ tables.region_production_table.title ]] [[ tables.region_production_table.subtitle ]] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [[ page_title ]] | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||||||

| Productions Totals | Fresh | Process | Total | Fresh | Process | Total | Fresh | Process | Total |

Global Highbush Processed

Report Team Narrative

While processed volume and market growth may have slowed somewhat since 2020 when consumers globally – from the U.S. to South Korea to Australia - hoarded frozen fruit in response to covid, the sector’s situation is still far more robust than before the pandemic when the processed industry had been enduring years of marginal growth and commoditization.

In May 2022 the level of frozen blueberry inventories in Public Storage in the United States - the category’s largest market - were up by around 3%, partly reflecting the year-on-year frozen sales decline in volume (-6.5%, tied to a decrease in North American frozen crop diversion) and value (-4.4%) reported by the U.S. Highbush Blueberry Council (USHBC) for 2021. Another driver may be what one industry veteran described as “the largest ever volume diverted on arrival” from South American fresh blueberries to the processed market. Shipping delays from South America put the quality of imports under pressure in 2021/22, at times leaving processing as the only option apart from wastage for some containers.

The ongoing opacity of global and national frozen inventories and grade transparency plays a perennial role in undermining market stability. With what is effectively a 24-month marketing cycle and a tendency for fruit to suddenly appear from “under a snowbank” (a large portion of the crop remains in private storage which is not reported publicly), inventory and pricing mechanisms for the frozen market can be challenging to track, especially as freezer reports don’t necessarily reflect the grade of the fruit. To illustrate, what can occur are reports of large inventories (e.g. the Public Cold Storage report, which reports volumes in public storage and includes fruit that is sold but not shipped) while packers are in fact struggling to source A-grade frozen blueberries. Despite the ample stock available on paper, there are still shortages of A Grade IQF polybag blueberries at retail in North America.

The relative improvement in the sector’s performance on 2019 levels however cannot be overstated, with the figures in 2021 demonstrating major double-digit growth over the two-year period in value and volume, perhaps also buoyed by speculation over greater losses than what eventuated following the heat dome in the Pacific Northwest. As referenced in the British Columbia section of this report, there were even moments when processed prices were higher than fresh.

Prior to the pandemic, observers had noted a divergence from the previous interlinkages between the fresh and processed blueberry sectors, but since 2020 it appears more of an equilibrium has returned after years of processed-oriented growers exiting the industry. Growers have the option of diverting to processed, both fresh byproduct and higher grade field product, processing plays a useful role in absorbing volumes – a critical channel as fresh blueberry plantings expand globally and the existence of fields with less desired varieties. This is particularly the case for high chill growers. Longer established plantings struggling to serve the fresh market are increasingly diverted to processed. The scaling of processed blueberries is working to the benefit of food manufacturers, juicers, and consumers who either have lower budgets or whose purchasing preferences are driven primarily by the berry’s high antioxidant content.

In regions such as the Pacific Northwest, growing, harvesting, and packing blueberries strictly for processed is also a competitive business model due to the high yields and mechanization of the systems in the region. Most harvesting for processed is already done by machine with sophisticated infrastructure established in mature industries where vertical integration and economies of scale are key; a business model that has risen in tandem with the fresh industry.

The IQF (individually quick frozen) market remains the primary target at the higher end of the processed market. This marks very little change over the last two decades with limited innovation on the product side among the growing, packing, and first handler side of the business. While there are exceptions, the majority of the value creation in processed blueberries is done by CPG companies (small and large) with the packing industry filling the role of an input supplier or at best a vendor of IQF polybags to retail. No doubt there is room for further downstream integration in the industry. Examples of this happening today include growing and packing companies introducing new dried and infused products as well as some new ‘fresh like’ ready-to-eat (RTE) products. Looking to the future it is not unreasonable to assume that there will be a substantial opportunity to create new uses for the market. The question remains as to whether this innovation can also be led by organizations which actually have established supply chains close to the raw product.

Industry efforts to boost consumption of processed blueberries are a key piece of the puzzle for lifting demand and returns for growers. As the product is less difficult to ship than highly perishable fresh blueberries, export market development is a logical pathway to lifting demand, but there is also a need to push more food manufacturing channels within categories such as baking, confectionery, smoothies and yogurts. To be effective, large-scale incorporation is required for this strategy to have a real impact as often a finished food such as a muffin or a protein bar has a very low gram-count of blueberries. What is also problematic is that whilst the fresh market is increasingly seeking out larger-sized berries, some food manufacturers such as bakers tend to seek out smaller-sized frozen blueberries, leaving less margin of error for fresh-oriented growers that shift to larger cultivars.

One sub-division of the processing industry that has struggled the most is juice-grade concentrate, for which inventories are at times high relative to demand. Unlike their peers in crops such as pomegranates, the industry has been unable to achieve the same levels of success for blueberry juice even though the product has similarly flavorful and high-antioxidant attributes. Worthy of inclusion is also the example of the Brazilian acai industry, which has capitalized on the Amazonian fruit’s high antioxidant content with acai bowls and smoothies sold in far-flung trendy cafes and eateries across the developed world.

North America remains the leading processed blueberry growing region and market, having practically doubled since 2010, but China’s processed industry is catching up after jumping three-fold between 2017 and 2020 according to the official figures. It is important to note that a disproportionate amount of China’s processed fruit is of low grade rabbiteyes destined for the juice and puree market. Processed blueberry exports from South America, most notably Chile, Peru and Argentina, have been increasing steadily as well in recent years and play second fiddle in the IQF industry after the leaders in the Pacific Northwest.

The wild blueberry industry is a sector that witnessed greater rises in price during the pandemic. It is understood that North American wild blueberry crops, concentrated in the continent’s northeast, have witnessed strong export performance to Europe where wild blueberry supplies have been hampered to some degree by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

| [[ tables.region_production_table.title ]] [[ tables.region_production_table.subtitle ]] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [[ page_title ]] | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||||||

| Productions Totals | Fresh | Process | Total | Fresh | Process | Total | Fresh | Process | Total |

| [[ tables.region_hectares_table.title ]] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [[ page_title ]] | Planting | 2021/2022 Production | 2021 Production | ||||||||

| Growth Totals | 2017/2018 | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 | Fresh | Process | Total | |||

| Growth Totals | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Fresh | Process | Total | |||

| [[ tables.region_production_table.title ]] [[ tables.region_production_table.subtitle ]] | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [[ page_title ]] | 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 | ||||||

| [[ page_title ]] | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||||||

| Productions Totals | Fresh | Process | Total | Fresh | Process | Total | Fresh | Process | Total |

| [[ tables.production_metrics.title ]] | |

|---|---|

¹ Growth in volume produced compared to previous season

² Volume increase from new hectares coming into production

³ Volume increase from higher yields

| [[ tables.tableExportsBySubregion.title ]] [[ tables.tableExportsBySubregion.subtitle ]] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subregion | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 |

| Subregion | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| [[ tables.tableExportsByPartnerSubregion.title ]] [[ tables.tableExportsByPartnerSubregion.subtitle ]] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subregion | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 |

| Subregion | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| [[ tables.tableExportsByReporter.title ]] [[ tables.tableExportsByReporter.subtitle ]] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 |

| Reporter | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| [[ tables.tableImportsByOriginSubregion.title ]] [[ tables.tableImportsByOriginSubregion.subtitle ]] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Origin | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 |

| Origin | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| [[ tables.tableImportsByReporter.title ]] [[ tables.tableImportsByReporter.subtitle ]] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reporter | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 |

| Reporter | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| [[ tables.tableExportsBySubregion.title ]] [[ tables.tableExportsBySubregion.subtitle ]] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subregion | 2018/2019 | 2019/2020 | 2020/2021 | 2021/2022 |

| Subregion | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

South America

Report Team Narrative

As Ecuador and Colombia now have nascent blueberry industries, the IBO team has collected the following information to complement the South America narrative.

Colombia

Colombia may not yet be a substantial player in the global blueberry industry, but the country’s close proximity to the USA and its ability to produce blueberries practically year-round have made it an emerging industry of interest, particularly considering Colombia’s recent proven export success in other fruit crops such as avocados, limes and physalis/goldenberries. The operation and logistics models of the highly competitive cut flower industry also provide both reference as well as strong horticulture industry operators. Historically, the focus of the industry has been on supplying domestic consumption, but as scaling continues export oriented activity is also beginning.

While blueberry cultivation in Colombia technically dates back to the 1980s, the industry’s incipient growth began in earnest in the late 00’s. Unlike the South American sector’s northward push into Peru that relied on low-chill genetics along the coast, the international ventures from Chile, the U.S. and elsewhere that entered Colombia have planted between 2,600-3,000 meters above sea level, under the moniker of ‘tropical blueberries at altitude’. The growing systems are more reminiscent of Central Mexico no-chill evergreen production but without the punctuation of seasonality.

Most of this production sits in the mountainous plains of Boyacá and Cundinamarca to the north of Colombia’s capital Bogota, where very little difference in daylight hours throughout the year allows for pruning to induce production as desired by farm managers. The remainder is split between the department Antioquia and in the country’s south near the border with Ecuador.

Blueberry plantings have increased almost tenfold since 2016 in Colombia with an industry that is now much larger than long standing South American producer Uruguay, for example, but still much smaller than Argentina, to put its size into perspective. There are an estimated 600 growers in the country but only three that have farms larger than 20ha. The largest of these is a Colombian grower that has accounted for the highest share of an incipient export program, predominantly focused on the USA. Larger plantings are in the pipeline over the next two years from domestic and foreign investors, including a joint venture with Australian proprietary varieties that intends to reach 50ha planted within two to three years as well as various American and Chilean supported ventures underway.

For now, Colombia is putting in the groundwork to develop production with a view to establishing a more aggressive export program in the years to come. Colombia’s population of more than 50 million has shown sufficient demand to absorb the volumes being produced, which are around 150MT per week in peak periods and 70MT in the season dips. Colombia has two production peaks – the first in December-January, and another in July-August. Peru, and to a much lesser extent Chile, also exported small volumes to the market last season.

The greatest hindrance to Colombia’s export ambitions at present is the protocol options for shipping to the USA, comprising either the less preferred methyl bromide treatment on arrival, or cold treatment in transit for 14 days. Colombian phytosanitary authorities have applied to their U.S. counterparts to accept a systems approach in areas with a low prevalence of Colombia fruit fly such as the Colombian savannah where harvests are concentrated. There are hopes that this will be achieved within one or two years, paving the way for a potential seven-day timeframe from harvest to arriving in the ports of Florida.

Ecuador

Ecuador’s industry is much younger, having begun in 2015 with its production spread along the Andes Mountains in various locations on both sides of the equator. There are also trial plantings in coastal areas such as Santa Elena, Manabi and El Oro; the latter two being more often associated with Ecuador’s world-leading banana export sector.

Around 95% of volume from Ecuador’s estimated plantings of 185ha are currently concentrated in the Andes, although only 50ha is currently in production. Both Ecuadorian and multinational companies are conducting trials and tests with new varieties with the goal of meeting demand in overseas markets. The varietal mix is around a third Biloxi, 27% Atlas Blue and 13% Emerald, with other varieties planted include Apolo, Stellar, Presto, Jewel, Legacy, Star, Eureka and Dazzle.

Almost all the volume grown is sold domestically, although the beginnings of an export program may be emerging as miniscule shipments were sent to Spain and Panama in 2021.

Mexico/Central America

Report Team Narrative

For an in-depth review of the leading producing countries of Mexico/Central America, please see the individual reports including official country member reports and IBO Report Team narratives for:

Below is a brief review on the other commercial source of supply today in Central America, Guatemala.

Guatemala

Whilst pre-clearance protocols have been approved by the U.S. Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) for blueberries from Guatemala - the only noteworthy producer of the fruit in Central America – the program has not yet come to fruition due to limited budgets and the need to train inspectors.

To date Guatemala has been limited in its export options, shipping small volumes to neighboring countries such as Honduras and Nicaragua, as well as to the U.S. where shipments need to have undergone treatment such as methyl bromide – a chemical that is difficult for growers to secure outside of programs administered by Guatemalan phytosanitary authorities. Fruit exported to the U.S. must also arrive north of the Mason-Dixon line, prohibiting imports in ports such as McAllen, TX or Miami, FL.

Since its emergence around 2005 and having been built on the variety Biloxi, the Guatemalan sector has been turning to new varieties and production techniques such as growing under tunnels with substrate. Volume is led by a small group of companies, most of which also produce blackberries, sugar snaps, and other produce for export. The growing regions are at a lower latitude but higher altitude than Central Mexico.

With a production window traditionally between November and February, Guatemalan growers have felt increased competitive pressure from Peru and Mexico, while their logistical channels to reach the Americas’ largest market - the USA - are more challenging. There are also limitations around the availability of large extensions of land suitable for the crop, so whilst plantings have grown somewhat in recent years it has been at a very slow rate.

Asia

Report Team Narrative

For an in depth complement to the happenings in the most established regions of Asia, please visit the following country reports:

Apart from China (See China Report Team Narrative) which is, according to official Chinese data, the world’s largest blueberry producer and a major import market, the only country in Asia with a sizable level of production is South Korea – a nation whose volume in 2020 was comparable to that of North Carolina.

South Korea’s production volume has been steadily increasing since overtaking Japan in 2016, doubling in size over the three years that followed to 2019. As per Mr. CS Rim’s summary, much of this growth has come from higher-yielding early season southern highbush varieties under tunnels as plantings mature, although the shift in timing has led to a return in interest towards earlier northern highbush cultivars for open field production. A lot of the varietal conversion in Korea is being led by a private nursery from the U.S. Pacific Northwest.

Between 2016 and 2020, South Korea’s imports rose by 42% with Chile accounting for more than four-fifths of volume and the US supplying almost all of the remainder. This put South Korea on a similar footing to Japan in terms of import market size, with the latter having changed little over the intervening period. More than half of Japan’s imports in 2021 were from Mexico, with other key suppliers including the USA, Chile and Canada.

For a country with a population of more than 125 million people, Japan’s per capita blueberry production and imports are now much smaller than their Korean neighbors and have been static for years. This may signal opportunities for growth with concerted efforts, especially considering Japan’s strong horticultural reputation in other crops such as strawberries. A British intellectual property management company representing university and private breeding programs in the U.S. currently has plants in Japanese quarantine, with plans to introduce new cultivars upon release.

Southeast Asia has been a focal point for market development amongst blueberry export industries worldwide, as evidenced by the fact non-protocol import markets such as Singapore – itself comparable in size value-wise to Japan or Korea – attract supply from all corners of the globe. In 2020 the USA was that country’s top supplier in terms of value, followed by Chile, Peru, South Africa, Spain, Morocco, and Australia.

At the time of writing there is no data yet available on the 2021 Singaporean import season, although one industry insider noted the logistical challenges with shipping lines worldwide had led to a greater insistence from supermarkets for air-freighted blueberries, with implications for those that traditionally ship via sea. Some of the blueberries Singapore imports from further afield arrive in Hong Kong first, and there were reports of delays in that final leg of the journey as well. As referenced in the Chinese section of this report, China has become an emerging presence in the Singaporean market due to higher volumes and a greater prevalence of blueberry varieties that travel well.

As noted in the U.S. section of this report, Southeast Asia is of great importance to both national and state blueberry bodies with promotional efforts underway. Outside of Singapore, Malaysia is another fast-growing market with imports doubling in the two years to 2020, with around a third coming from South Africa, with other key suppliers including the USA, Spain and Argentina, while Mexico is expected to become more dominant in years to come. Malaysia has seen similar trends regarding a preference for air-freighted blueberries, but importers report improved flight connectivity over the past 12 months which has increased the options available. Similarly to what has occurred in China, blueberry consumption in Malaysia has expanded to second- and third-tier cities where double-digit sales growth has been occurring and cold storage infrastructure is available.

Thailand and Vietnam are also rising in stature as blueberry export destinations, with New Zealand as an important supplier to both, while Peru has a prominent position in Thailand and the USA is increasing its presence in Vietnam.

Southern Europe/North Africa

Report Team Narrative

Between the rapidly expanding industry of Morocco and the Mediterranean’s traditional mainstay of Spain where production is concentrated in the province of Huelva, the European market has an ample late winter/springtime supply of blueberries between February and May. Both nations already produce fruit in smaller volumes well before that, but aggressive varietal conversion and planting programmes mean significant volumes may well be hitting the market from Morocco and Spain some 15 days earlier than usual within the next three years, in addition to flattening out the peaks and troughs through higher-yielding, crunchier fruit in the mid- and late-season.

The relevance of these two countries to the global industry’s growth was underscored late last year by the acquisition from the world’s largest blueberry company, Hortifrut, of one of Spain’s leading growers and breeders, Atlantic Blue, which owns a number of highly successful cultivars as well as operations in Morocco.

Around 1,200km south of the Moroccan blueberry industry’s previous southern frontier in Agadir, the pursuit of earliness is also underway in Dakhla within the territory of Western Sahara; a disputed region but one that has recently been emboldened by Spanish recognition and plans to open a United States consulate.

From Dakhla to Dakar, some international blueberry companies and investors are also emerging from the covid-induced travel lull to re-explore future opportunities in Senegal – a further 1,000km south - where trials that previously took place confirmed a blueberry-growing environment similar in latitude to the Mexican state of Jalisco (though lower elevation), allowing for two harvest periods including a very early window in September. Another peripheral zone of exploration is Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, where trials are taking place aimed at summer blueberry production with mid chill and high chill northern highbush varieties in hopes they will perform commercially due to the altitude.

On the later side of the seasonal spectrum, Portugal is growing steadily and is increasingly featuring in the plans of blueberry marketers, retailers and breeders wishing to capitalise on the market shortfall in June before Serbia, and later Poland, supplies the market. The northern Italian region of Piedmont commences in late June, while a prospective industry is emerging in southern Italy, particularly in Sicily, where season timing coincides with Morocco’s peak in March.

Portugal in the ascendant

As a long country with diverse climates within a short distance, Portugal is fast becoming a viable blueberry supply alternative for European supermarkets in the late spring, early summer period, featuring in the origin stable of a few major global grower-marketers.

The geography in Portugal is such that one could have a low-chill blueberry farm within just a few hours’ drive of a high-chill variety farm in the country’s north. Southern Portugal has a similar although milder climate to Huelva with much production under protected tunnels, whereas in the hilly north there are more open field farms with mid-chill and high-chill varieties such as Duke and Legacy.

As has been the lesson learned elsewhere, an industry can only survive on lucrative windows for so long and Portugal’s success will depend on its ability to adopt next-gen varieties – a process that is currently happening with cultivar from a handful of major players. Like Spain but not growing quite as early, Portugal has the advantage of proximity to major European markets and can produce fruit from March until the end of July, although with pruning of modern genetics it is possible that smaller quantities could be made available in October in direct competition with Peru.

The industry struggled with labor availability last year due to covid-related restrictions, and in response some growers are now turning to machine harvesting, although that trend is unlikely to appear in northern Portugal where farms tend to be small and on slopes with narrow roads.

In 2021, growers were able to attract strong prices in June until Serbian fruit arrived in the market. The Portuguese market itself is small with a population of just 10 million, but one of the country’s largest blueberry-growing companies experimented with direct sales in Lisbon, often achieving better prices than in export markets. This has triggered greater engagement with Portuguese retail, such as Pingo Doce which is working closely with domestic food producers to develop its own brands with ‘buy local’ cache.

Italy as a prospective market and production source

Off a low base, Italian blueberry consumption has grown 20% annually for the last two years due to growing health awareness during covid, increased domestic production and imports. In northern Italy’s largest cities blueberry consumption per capita is close to that of northern Europe, although in the south the fruit is far less known by consumers.

This is starting to change though, with Spanish exporters for example increasingly finding market outlets in Rome and further south, while a boom is underway in southern Italy for the production of southern highbush varieties in regions such as Sicily, Calabria and Puglia, spearheaded by large cooperatives from the country’s center and north.

Transportation is a problem though, with it often taking longer for fruit to reach the north from Sicily than it would from Spain.

Southern Italian blueberry production is a very recent development, and was virtually non-existent five years ago. From an industry that began in the 1960’s as a frozen-focused sector in Italy’s northwestern Piedmont region, the cooperative-led horticultural model Italy is known for has driven most of the production increase in the north, mostly in the pre-Alpine climes of Piedmont and Trentino.

Piedmont itself exports fresh blueberries to parts of Western Europe in a lucrative niche window in late June, early July when EU production is not so high. Modern, high-chill genetics are in demand in the region with varieties being grown from two Oregon-based genetics companies. Growers of other fruits such as peaches and kiwifruit, the latter having been through a difficult decade or more with vine-killing disease Psa, have also been converting their fields to blueberries in central and northern Italy.

Eastern Europe

Report Team Narrative

For an in-depth complement to what is happening in Eastern Europe please visit the following country reports:

With the longstanding Polish industry accounting for the lion’s share of production and continued growth (See Polish country member summary and report team narrative), Eastern Europe is home to rapidly developing blueberry industries whose young plantings are still in the maturing phase with plenty of volume increases on the horizon.

Spread across a wide geographical expanse – which in this report also includes the Republic of Georgia, a nation technically outside of Europe but to the west of the Caucasus Mountains – Eastern Europe comprises an agglomeration of culturally and climatically diverse nations that have found opportunities in blueberry markets, particularly in Europe and Russia, and to a lesser extent the Middle East. As part of the global trend towards 52-week supply, Eastern Europe itself - especially Poland - has also become a key market in its own right for exporters from the Southern Hemisphere, the Mediterranean and North Africa.

Some of the most aggressive planting has taken place in countries that cater to the June lull between the Spanish season and when large volumes come on in July from Poland, Germany and the Netherlands. The most notable rises targeting this window have come from Romania and Serbia, but there are other smaller pockets of development such as Kosovo, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Ukraine

Ukraine, with a blueberry season that largely overlaps with Poland, has also seen pronounced production rises over the last few years coming from an industry that is relatively sophisticated with sizable operations utilizing modern cooling facilities and sorting lines. There is a greater share of large operations – most of which come from Ukrainian capital, although there are a few from Russian and Kazakh investors – but smallholder farmers have followed suit with tiny plots, similarly to what has occurred in Poland.

Prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022, the industry was preparing for further investments in advanced infrastructure but since then has been in “survival” mode; a small portion of Ukrainian farms near Kyiv were damaged by military action, but 90% of fields are concentrated west of the capital where the situation has not been as severe, albeit not free from Russian shelling.

At the time of writing, there are concerns about transportation difficulties into the EU for Ukrainian blueberries when the season begins, given the logistical challenge of needing to change trucks and drivers at the border because of the prohibition on men leaving the country, not to mention the effects of inflation including the higher price of a variety of inputs including gasoline. Over the past two years the Ukrainian market has also proven attractive for local growers, at times offering higher prices than export markets, but amidst the war the purchasing power of citizens has been greatly reduced, which has major implications for that domestic sales outlet. The Ukrainian Berries Association has also been hampered in its ability to collect fees from members, limiting its financial capacity to undertake the kinds of educational activities aimed at furthering development. The association’s leadership is based in Poland at the time of writing, and has been working hard to both support the industry and raise charitable funds to help displaced Ukrainians.

Russia

Prior to the war Russia had seen a 25% increase in blueberry planting area year-on-year in 2021, albeit off a low base, and there was a great deal of interest from farmers in a variety of regions to adopt best-of-breed production methods and varieties; the industry at the start of this year could have been described as at an inflection point with domestic producers eager to capitalize on strong demand between import windows. Imports were growing at double digits with Peru as its leading supplier, followed by Morocco, Chile, and then Serbia close behind. Russian import growth from the Republic of Georgia was also surging as that industry’s main export market, although due to the tension between both countries there is a preference amongst Georgian growers to shift their market channels to Europe, the Middle East and Asia. Russia stopped reporting official data following the invasion, but data from Eurostat indicates the country’s imports in fact rose year-on-year in the first three months of 2022. There are reports of long lines at the border of trucks for the exchange of shipments, as European trucks are not allowed into Russia.

Serbia

After Poland, Serbia has the second-largest planting area for blueberries in Eastern Europe although volume-wise it sits just behind Romania. Serbia’s mountainous terrain allows for the manipulation of harvest windows with different varieties, although the predominant cultivar is Duke. Most growers are smallholders, but most exports are from large farms which also source volume from third parties in their local areas.

Some of the more advanced blueberry establishments in Serbia involve investment, resources and expertise from the Netherlands, the United States, the United Arab Emirates and Germany. At least half of the nation’s exports are attributed to a handful of companies. More than half of Serbia’s fresh blueberry exports in 2021 went to the Netherlands, followed by Russia, Germany, the UK and Poland.

Private genetics companies and growers from outside the country are dipping their toes into the Serbian market to train farmers with the necessary skill sets before taking the plunge into partnering on larger-scale commercial programs for proprietary varieties.

With a lack of data and transparency within the industry there are varying views about the extent of certain cultivation methods such as pots and substrate, although on the most conservative estimate at least half are producing this way, and a growing portion have anti-hail nets too. In some hilly areas in the south and southwest the soil is optimal for blueberry production and is conducive to growing larger berries that command price premiums.

Kosovo

Kosovo’s industry is closely connected to Serbia despite their checkered past. As far as the sector is concerned, “both countries fly under the same flag of blueberries”, as one industry leader noted.

The Kosovan blueberry industry was developed with support from USAID over the course of a decade, and after that programme recently ended the Swiss Government-affiliated Caritas took up the baton and has been helping small farmers with a programme that will last until 2025. Kosovo’s production has been growing rapidly with a window that is normally between late May and July, although the season commencement was 10 days late in 2021, meaning exporters missed out on a window with the best prices. A heatwave also led to damages for late varieties such as Liberty and Aurora (in a country where, like in Serbia, the leading variety is Duke), but those with fog systems were able to avoid the damage. Most growers were not ready for this form of protection though, as they had just been through a severe hail event in 2020 when half the crop was lost, prompting widespread investments in anti-hail nets that are now estimated to be in use for around half the planted hectares.

Kosovo has a similar cost per hectare to Serbia. Its percentage of substrate production in pots is lower at 25%, but growers who plant in fields still use white peat as substrate and yields are currently higher than in Serbia with aspirations towards a Dutch-style, high-density industry.

Elsewhere in the Balkans, other emerging blueberry industries include Bosnia & Herzegovina and Croatia.

Romania

To the east of Serbia, the bulk of Romania’s production is in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains on either side of the range, with the season running a week later than Serbia in the south and two weeks later in the north. This allows for harvests from mid-June to late August.

There are more than 300 independent growers in Romania, most of whom are smallholder farmers, but the handful of larger operations that exist are working towards becoming a cooperative with advanced irrigation systems, automated packhouses and modern sorting technology. Some are also experimenting with next-gen varieties from the United States, Spain and elsewhere.

Romania has the added benefit that it can draw on a workforce who already have years of experience working on blueberry fields in Spain, and can return to Romania to continue working once the Spanish season is finished each year. As is the case everywhere, the Romanian industry is battling with input inflation, but that hasn’t stopped interest from new investors including a Canadian company that is assessing the viability of a large development by Romania’s standards.

Republic of Georgia

On the opposite side of the Black Sea from Romania sits the Republic of Georgia, a nation that has only been experimenting with blueberries for less than five years and is on the precipice of massive growth, mostly in the form of southern highbush blueberry varieties although the mountainous topography allows for northern highbush growing in certain areas. With tunnel production the industry is capable of growing the fruit in May, but the season is concentrated in June and July with some volume in August. The bulk of plantings are in western Georgia in the regions of Guria, Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti and Imereti.

The typical farm in the Republic of Georgia is one hectare or less – a tendency that has been encouraged by government grants to smallholder farmers to plant blueberries, mostly with older varieties as well. As such a new industry, there is a wide gap in knowledge which is not helped by the fact most educational materials are not in languages that are very accessible to the average Georgian farmer. There are an estimated 40 farmers in Georgia who have blueberry farms that are larger than 20ha.

In parallel to the trends across Eastern Europe, the proliferation of small growers detracts from the fact that most of the blueberry volume comes from larger entities, which in Georgia is about 90%. There are an estimated 40 farmers in Georgia who have blueberry farms that are larger than 20ha. As has been the case in Serbia there has been investment into a large farm from a UAE-affiliated entity, as well as investors from India. In 2020 one of the world’s largest blueberry breeders and nurseries from the U.S. set up shop in the country, with around 11 next-gen varieties under trial. Growers also are known to source plant material from Polish nurseries.

There is further opportunity for large operations to be developed as well thanks to another government programme committing grants towards seedlings and irrigation systems for citizens on plots of land between 0.5ha and 50ha. This can be for any crop, including blueberries.

Western and Central Europe

Report Team Narrative

For an in-depth complement to what is happening in Western and Central Europe please visit the following country reports:

As one of the world’s fastest-growing fresh blueberry markets, Western and Central Europe is a region that has seen a steady rise in production over the past five years as growers turn their attention to soft fruit. Growth is coming from both a proliferation Europe-wide of small growers and a spattering of larger-scale operations; in both cases there is usually prior experience in berry farming with other crops such as strawberries or raspberries, and there is an eagerness amongst certain segments of national industries to adopt new genetics to meet demand from retailers for firm, large and flavorful berries, in addition to climate-adaptability considerations.

Weather was problematic across most of Europe in 2021, with rains impacting the shelf life of blueberries in the Netherlands and Belgium, as well as central and northern Germany. For the second time in three years, the French blueberry industry was struck by damaging frosts; an issue that is accentuated for that country because the largest concentration of growers in the southwest near Bordeaux have prioritised early production in their varietal selections, implying a greater share of bushes in bloom when spring frosts occur. Dutch growers also suffered from bird-related damages to fields, which were more severe than normal due to a lack of clarity in government policy on the issue.

With a relatively smaller area in the context of the region, the Netherlands has been one of the hotspots of blueberry investments in Western Europe, and the decline in production in 2021 is likely to be a dip in an upward sloping volume trend in the years to come. Dominated by five organisations that market most of the crop, around 90% of Dutch blueberry production is open field, sometimes with hail or rain covers. As an advanced agricultural nation that is home to a disproportionate amount of plant breeders generally for its size, it is unsurprising that the Dutch are so embracing of new varieties. Producers typically will not hold on to a particular cultivar for more than six years as they seek to rapidly innovate. Until the current inflation crisis there was also optimism surrounding incipient greenhouse innovations for blueberry production under lights, but investments in this cultivation model have been put on hold given the higher cost of energy.

Last year the Netherlands was Europe’s largest importer of blueberries as well (albeit as both an import market and predominantly a re-export hub), followed by Germany, which itself was only just ahead of the UK. Most markets in the region recorded high blueberry import growth rates in 2021, with the largest percentage increases seen in France and Sweden. Germany actually imported less volume but its value of blueberry imports rose slightly. In the past few years it is estimated the penetration of blueberries in the German market has risen by around 45%, and another trend has been German retailers introducing larger pack sizes, including 500g and 750g packs in some stores at certain times.

On the topic of packaging, a potential barometer for where Western European countries might be heading on tackling plastic waste is the impending ban in France within three years on single-use plastic punnets – a traditional mainstay for the sale of berries, and one which most industry experts believe cannot be matched by other packaging materials in terms of shelf life, quality and presentation. What may be encouraging however is that Grand Frais – a relatively newer French retailer that has had great success in a saturated market, built on a premise of fresh foods and vertical integration - has introduced bulk blueberry formats (similar to what one would normally see with apples) accompanied by a scoop, and this has reportedly resulted in consumers making larger blueberry purchases.

In France itself, production is nowhere near large enough to satisfy demand. Year-on-year production in the country doesn’t change much either, although newer plantings could mean there is latent growth potential. As noted earlier, volume is concentrated in the southwest but the fruit is grown all over the country. Closer to Paris is a large project by French standards that has been developed in Anjou in partnership with a British firm, while later season fruit is also grown around Lyon and in the mountainous Clermont-Ferrand area. At the time of writing, an agricultural census that finally gives blueberries its own category is due for release in 2022, which will provide a better understanding of the true planted area for the crop.

Across the channel, the UK’s ability to produce domestically-grown blueberries has been threatened by pressing labour challenges following Brexit (see UK Country Member Summary for a more detailed analysis). Many Polish workers who used to pick fruit in the UK are increasingly choosing Germany and other EU industries instead as it is easier given the UK’s migration regulations. Across the continent is greater demand for machine harvesters oriented for the fresh market, with one Dutch developer of the technology noting they are easily able to sell every machine they make. The adoption of machine harvesting for fresh is nowhere near as common in Europe as in North America, but some industry pundits believe that if proven successful it could suddenly make larger-scale Western European blueberry production much more viable than it is now, especially given labour scarcity and costs.

Local-for-local has become an important retail trend throughout Central and Western Europe – and for much of the former Soviet Bloc as well - that is incentivising new plantings that target the local market, even if the season is short or the yield is not particularly high. In this context, the blueberry business has become lucrative for farmers who already have high yields that compensate for high labor costs, as more secure local programs give them one less headache to worry about with much more certain cash flow.

It is a trend seen amongst a subsection of retail and other channels such as community grocers and farmers’ markets. Whether it’s in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France or elsewhere, there are supermarkets that showcase local fruit – including blueberries – as a differentiator during the local season, and those that are more focused on price discounting. The local-for-local trend is driven by two broad demographics: one, mostly older, who care about local for local’s sake; and two, generally younger, for whom carbon footprint is most important so the country of origin may not be as relevant as how far the fruit has travelled.

Quality Premiums: There is a second retail divide as well, and not necessarily overlapping with the local trend, that marks the stratification of varieties. Certain retailers will pay for, and sell at, a premium for particular characteristics often exhibited by proprietary genetics or for blueberries from supply partners with a reputation for consistency regardless of fruit origin. Then there is the other half of retail that is more price-oriented and is willing to accept lower quality fruit from older varieties.

The dominance of private labelling in continental Europe and the UK is also a challenge, although not an intractable one, for encouraging marketers or growers to adopt premium genetics. Under this system their brand will not be consumer-facing and their product can be lumped in with other suppliers and the fruit characteristics may not be consistent. That said, some marketers have been able to successfully demonstrate the value of their brands and be given the privilege of their own consumer-facing marketing amidst the sea of private labels. What the entire removal of plastic packaging would mean in this area is uncertain, although there could be an unexpected positive effect – for blueberries to succeed under the more strenuous treatment conditions of bulk shelves or cardboard packaging, the imperative for improved genetics with an emphasis on durability becomes greater, although as other horticultural industries such as tomatoes learned the hard way – breeding for durability alone is a terrible idea when what the public wants is flavor as well.

Africa

Report Team Narrative

For an in-depth complement to what is happening in Africa please visit the following country reports:

Zimbabwe

In moves that mimic what Chilean expertise brought to Peru and elsewhere in Latin America in recent decades, South African growers or companies with a strong presence there are branching out northwards towards the equator in pursuit of other production windows and supply diversification.

A prime example is Zimbabwe, where growth in percentage terms looks set to outpace South Africa, albeit off a lower base. Firm hectarage data is difficult to ascertain, but many large players have either run trials or have already begun commercial-scale plantings. This is in addition to local growers, many of whom already have experience in other intensive horticultural crops like snow peas and sugar snaps, forming alliances to export. Healthy infrastructure exists in Zimbabwe with cold storage facilities at Harare’s international airport, and president Emmerson Mnangagwa – who replaced Robert Mugabe after his 37-year rule came to an end in 2017 – has shown an amenable attitude to agriculture.

The Zimbabwean season tends to begin in mid-to-late May although early volumes can commence as early as April. As has happened in many new industries, sizeable plantings of Biloxi and Ventura blueberries are in the ground, but in light of the aforementioned logistical and economic challenges that place greater emphasis on shelf life, most new plantings are with new genetics and several of the world’s leading genetics IP holders are present in the market.

Namibia

Plantings and trials are also underway in Namibia, where a US-South African joint venture US genetics from a leading US genetics company accounts for the largest surface area of plantings has been investing into production, around Rundu in the country’s north close to the border with Angola. Fruit from these farms is sent by truck to Johannesburg, where it is air-freighted into destination markets. In the desert region of Aussenkehr in southern Namibia, known for its table grapes, there are comprehensive substrate trials taking place involving varieties from a handful of global genetics programs, some of which serve to showcase new cultivars to visiting producers from South Africa if they haven’t yet passed through quarantine there.

Zambia

Growers and investors are trying their luck in Zambia as well, which in July 2020 became the first African nation to gain direct access to the Chinese market with the first shipments sent in November of that year. Since then however, it could not be confirmed whether any sizeable trade with that market has materialized. New developments have not been expanding as aggressively as in neighboring Zimbabwe, although some trials led by outside experts have progressed to the commercial stage on a small scale.

Other Origins

Further north, trials are taking place in the equatorial states of Uganda and Kenya where there is potential for production from March to May, with the potential to double crop on evergreen low chill varieties if desired.

US & Canada

Report Team Narrative

Here we provide an in-depth review of the state of the industry in the United States and Canada. Please visit the following country reports: