Peru

Country Member Summary

Adapted from a Report by the Peruvian Blueberry Growers & Exporter Association, ProArándanos

2021-22 Campaign

Peruvian fresh blueberries once again managed to top the world’s export rankings in 2021-22, giving cause for

optimism on the path to 2022-23 despite the challenging moment the agricultural export industry is

facing.

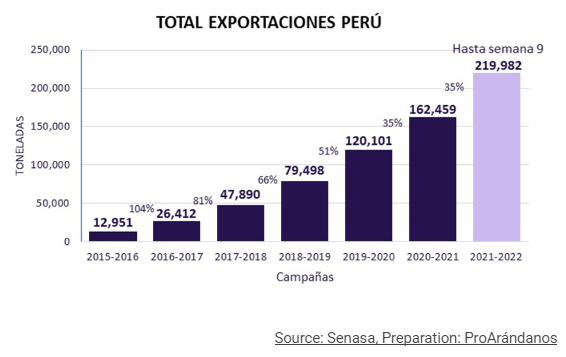

Having exported a total of 12,951 metric tons (MT) by the close of the 2015-16 campaign, Peru grew to export

219,982MT in the recent 2021-22 season, consolidating itself for the third consecutive campaign as the

world’s leading fresh blueberry exporter.

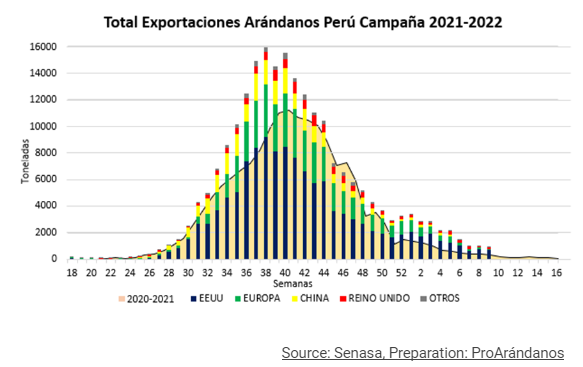

The export peak during the 2021-22 season occurred in week 38 with a total of 15,981MT, representing an

increase of 42% compared to the previous season peak of 11,240MT in week 41, or an increase of 108% in

comparison to the peak in the 2019-20 season when 7,689MT were exported during week 45.

It is also worth noting that during the 2021-22 season there were 16 consecutive weeks (weeks 33 to 48) when

exports greater than 5,000MT were registered; in the 2020-21 season this benchmark was achieved for 15

consecutive weeks (weeks 34 to 38), while in the 2019-20 season it was for 12 weeks (weeks 37 to 48)

It is estimated that 8% of the total fresh blueberry volume exported from Peru was organic, with the U.S. as

the main destination market.

In terms of annual values, during 2021 Peruvian fresh blueberry exports were more than US$1.2 billion

(Source: Sunat), reflecting growth of 23% versus 2020, a year when US$983 million was exported. This growth

has kept blueberries in second place in the ranking of Peruvian fruit and vegetable exports, surpassing

fresh avocados, positioned only behind fresh grapes which were just shy of US$1.26 billion.

Main International Markets

The main export destination for Peruvian blueberries during the 2021-22 season was the United States with a

55% share of the exported volume, followed by Europe (ex-UK) with 24.37%, China with 12.18%, the UK with

5.82%, and others with 2.63%. Overall, Peru shipped blueberries to 31 countries worldwide.

There were 120,992MT of fresh blueberries exported to the United States, representing a 40% increase on the

previous season when 86,385MT were exported.

Shipments to Europe (ex-UK) reached 53,603MT, representing an increase of 17% compared to the previous

campaign in which 45,969MT were exported.

Exports of fresh blueberries to the British market totalled 12,810MT, representing an increase of 20%

compared to the previous season, in which a total of 10,712MT were exported.

In terms of China, exports to this market reached 26,786MT, representing an increase of 68% compared to the

previous season, in which a total of 15,908MT were exported. In percentage terms, the Chinese market has

increased significantly more than the United States, Europe or the UK during this campaign; at the same

time, in absolute terms it has grown by a little bit more than 10,000MT – a figure that is close to the

growth in shipments to Europe (including the UK), which rose by 9,000MT compared to the previous season.

During the 2021-22 season, a total of 1,657MT of fresh blueberries were exported via air freight,

representing 0.75% of the total exported volume. This air freight volume was up 3.09% compared to the

previous season in which 1,607MT were sent via this channel, representing 0.98% of the total volume sent in

the campaign.

Determining factors for Peruvian export supply

Climate and optimal genetics for blueberry production are determining factors for our export offering.

Specifically for blueberries, an optimal temperate climate (desert-arid-subtropical) exists across almost

the whole coastal region, from Piura to Tacna, and from the Pacific coast to approximately 2,000 metres

above sea level.

This temperate climate, characterised by the absence of rain (the annual average is 150mm) and an average

annual temperature of 18° to 19°C, which is lower at higher areas, ensures good quality and is highly

relevant for the precocious production of blueberries, making varietal replacement trials much faster than

in other places.

All of this, adding to an agile phytosanitary control organization and the professionalism of Peruvian

operations (human capital, technology and innovation), have accelerated the growth of our blueberry

exports.

Blueberry export evolution over the years

The industry has evolved rapidly, with exponential growth in exported volumes during certain weeks of the

year and with an expansion of the blueberry growing area to more regions in the country. This is very good,

as the employment generation is reaching more regions in our country.

This exponential growth in recent years – more than 16-fold in seven years – has been accompanied by a great

responsibility and commitment to continue representing the good name of Peru, ensuring we meet the highest

standards of quality and good agricultural, social and environmental practices, as well as refreshing our

brand image as promoters of Peruvian blueberries.

Varieties in the 2021-22 export campaign

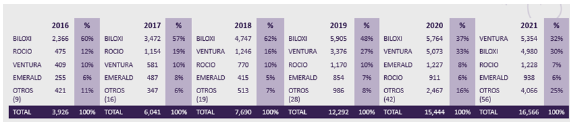

In 2016, Peru had 13 different blueberry varieties and Biloxi represented 60% of total plantings.

In this campaign there were around 60 different varieties of blueberries and Biloxi was in second place,

representing 30% of total plantings in Peru, after the variety Ventura which occupied first place,

representing 32% of the total.

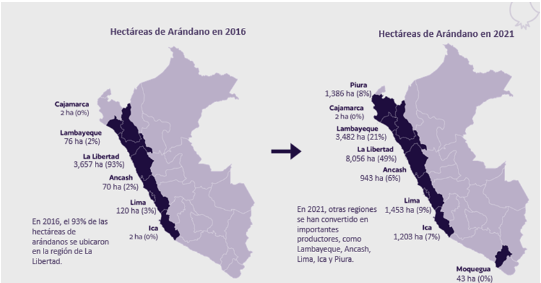

Main growing regions in the country and their participation in the export dynamic

During the 2021-22 campaign, La Libertad had a representation of 54.11%, consolidating itself as the most

significant region in exports of this crop, followed by Lambayeque with a representation of 21.16% and Lima

with 7.98% of the total.

In terms of the area planted at the close of 2021, there were 16,566 hectares certified with blueberries,

representing an increase of 7% (1,123ha) compared to 2020 when 15,444ha were registered. Between 2019 – a

year when 12,292ha were registered – and 2020, the increase was 26% (3,152ha).

Leading the way to a promising future

During the 2021 campaign the markets of India and Malaysia were opened, and we have been working to open the

markets of South Korea, Japan, Indonesia and Vietnam.

Turning to 2022, as Proarandanos we continue working to access more markets and with better conditions,

maximizing our communication channels to strengthen the positioning of Peruvian blueberries, providing more

statistical information and forecasts to enable a more informed industry; similarly, we continue working

together with the State, through the leadership of AGAP to ensure the necessary conditions are provided for

the production and exportation of blueberries.

In the same way, we keep focusing our efforts on the efficient management of natural resources, good

agricultural practices, and above all, the respect and appreciation of our workers, their families and

communities.

ProArándanos has prioritized the following areas of action in its agenda for the coming years:

- Access to more markets with better conditions: action together with Senasa

- Increasing consumption in the main markets, working together with international stakeholders.

- Ensuring the necessary conditions for production and exportation, coordinating with the public sector through

AGAP – the Association of Agricultural Grower Unions of Peru.

- Enabling a more informed industry with regards to statistics and forecasts, as well as social and

environmental impact indicators.

- Sustainable development: fomenting the efficient management of natural resources and good agricultural

practices.

Peru

Report Team Narrative

The global opportunity to serve higher year-round global blueberry consumption is exemplified by the recent

strong performance of the world’s largest exporter of the fruit, Peru, which was an industry minnow just a

decade ago when it wasn’t even in the top 30 blueberry-shipping nations worldwide, registering gross sales

of less than $500,000 in 2012.

As referenced in the detailed Peruvian country member summary prepared by ProArandanos, the country’s

fresh blueberry exports surpassed $1.2 billion in the 2021 calendar year.

This figure encompasses Peru’s peak shipping window of late August to October, although shipments can

start as early as late May/early June and finish in April of the subsequent calendar year.

Export volume rose by more than 35% in the 2021-22 season, and returns held up remarkably well

considering the influx of volume and unprecedented, pandemic-induced logistical delays that set back

shipping arrival times from a matter of days to several weeks in Peru’s key overseas markets.

In the U.S. for example, the average price for Peruvian blueberries was higher year-on-year for the

first seven weeks of the season, while from late August until mid-January the fruit was selling for

higher prices than market averages every week relative to other sources of supply.

This speaks to the consistency that Peru has come to represent as a supplier to the global markets.

Most of the volume growth in 2021-22 occurred between August and October, reflecting a strategy to

target periods of relative scarcity between the North American/European seasons and the Chilean campaign.

It is a strategy that has been implemented through a combination of geographical diversification within

Peru, varietal selection and pruning methods to manipulate harvest times. It is interesting to note the

industry’s peak export volumes occurred three weeks earlier in 2021, and that the share of the nation’s

two leading varieties – the ‘older’ cultivars Biloxi and Ventura – fell by eight percentage points to 60%,

illustrating the rapid take-up of new varieties with improved durability, sizing, texture and flavor;

a transition that has been accelerated by competitive pressures from South Africa, a producer that is

known for its widespread adoption of proprietary genetics and positive quality perceptions in the

European market. Anecdotally, Peruvian exporters have been increasingly selecting newer genetics with

longer shelf life and greater firmness and brix for shipments to the more demanding Chinese market.

As a side note, in mid-2022 the Peruvian industry achieved an opening of Israeli fresh blueberry market

access.

Practically all the world’s leading blueberry genetics companies offering southern highbush

(Low and No-Chill) blueberry varieties have a presence in Peru, with the number of registered varieties

rising by 30% in 2021 to 60. Some are more incipient than others, including a local breeder that has been

expanding, while at least one of Peru’s top grower-exporters has a blueberry breeding programme based in

the country.

Chilean, Spanish, and U.S. horticultural experts played a pioneering role in the Peruvian blueberry

industry’s development, just as they did previously in table grapes, successfully executing a

transformative vision in what a decade ago was viewed as an unorthodox region for growing the soft fruit.

The opportunities of earlier production thus attracted more foreign entrepreneurs and investors who went

with the tide rather than fighting against it, along with Peruvian agricultural companies that have since

become industry leaders, some of whom have undertaken ventures north in the same expansive, pioneering

fashion to produce blueberries in such countries as Colombia and Mexico.

Almost half of Peru’s blueberry plantings are in the department (province) of La Libertad, more often known

for the city of Trujillo – a desert region whose agricultural sector was activated by the Chavimochic

irrigation project in the late 90s with a boom in asparagus production, but since then blueberries have

become a much more attractive investment.

More recently in 2014, the opening of the Olmos irrigation project in the department of Lambayeque heralded

a new agricultural revolution in the Peruvian desert, prompting ambitious, large-scale projects in

numerous crops including blueberries. Today the region accounts for more than a fifth of Peru’s blueberry

hectares in production, offering a a more natural ability to produce in an earlier window than La Libertad.

La Libertad’s share of blueberry-growing hectares has declined from 93% in 2016 to 49% in 2021, as part of

a geographical diversification trend that has reinforced the country’s push towards extended production

and its ability to grow more during particular market windows. Combined, the southern region of Ica, the

region of Lima encapsulating the nation’s capital and its surrounds, and the northern region of Piura

bordering Ecuador, account for almost a quarter of Peru’s surface area for the crop.

Broadly speaking, coastal Peru has a mild climate with very little variance in temperature; the same is

true for the northerly, early-producing Piura, but within a higher temperature band. In atypical years

however when temperatures are slightly higher in the summer, as was the case for the 2021-22 season,

certain varieties tend to be triggered into plant growth with delays in flowering and hence, fruiting.

This underscores how critical varietal selection can be in the warmest of climates; cultivars that can

tolerate or adapt in such conditions do exist and are increasingly being planted in the area.

The number of hectares planted in Piura more than tripled in 2021, with growers attracted by the region’s

adaptive soils, water chemistry and, most importantly, earlier harvests that tend to garner higher market

returns. The Piura season begins in May and peaks in late September-early October, unlike Peru overall

which peaks in mid-October. The humid and muggy conditions can create new challenges, making it essential

to pick fruit as close to dawn and dusk as possible.

The department of Ica, which like La Libertad has been a bastion of first asparagus and then avocado

industries, saw its blueberry-growing area rise by almost 60% last year. High-density plantings in

substrate pots are less common in Peru where most coastal production is open field, but the very salty

soils in Ica warrant alternative growing methods that are more in line with what can be seen in southern

Morocco or Mexico. Many of these projects harness reverse osmosis units to address water chemistry for

irrigation, which is especially critical for achieving optimal pH levels and electric conductivity in

substrate growing systems.

The percentage share of organics rose by three percentage points to 8% in 2021 as the industry pursues

what is perceived as an attractive proposition in the North American market, with many growers reporting

healthy premiums despite marginal falls year-on-year. In the larger context of the Peruvian industry,

the 8% share represents a significant increase in the offering versus prior years and is the product of

decisions made several years ago given the lag time in converting conventional fields to organic and

securing certification. It is important to note that growing organic in Peru is uniquely challenging due

to the lack of a ‘kill cycle’ for pests and disease as well as the challenge for securing inputs to

manage in evergreen systems. Organic fields in Peru tend to have lower average yields than conventional

fields in Peru, which is not always the case in other competitive organic growing regions.

Growers throughout Peru became more reluctant to plant new fields since the election of President Pedro

Castillo last year. At the time of writing, the administration has not enacted any policies that

specifically damage agriculture, but rather the tone towards business and agriculture have led to

uncertainty. Blueberry planting has recently been revived in Peru, which has among the highest yields

for the fruit globally, but it is believed that the speed of new plantings would have been much faster

had Castillo’s opponent won. The political climate also has implications for infrastructure developments

and upgrades that have been idle for years, and are likely to remain so in the current environment,

including irrigation development plans such as the Chavimochic expansion and the Majes Siguas project

near Arequipa. These delays in infrastructure will likely impact the capacity for the industry to expand

in high value horticultural crops in the medium term. Nonetheless, the data shows almost 20% of Peru’s

planted hectares for blueberries are not yet in production; fields of new varieties are still maturing and

the impact of that, ceteris paribus, will be continued volume growth over the medium term.

Peruvian growers emphasize that the political uncertainty is not just limited to them but is an issue of

concern throughout South America, as is the consensus that logistics delays and costliness are the most

pressing problems facing the industry right now. These conditions have forced operators to be more

flexible in how they react to changing shipping schedules and port conditions, while also diversifying

their shipping options. Most of Peru’s 2021-22 volume had been shipped by the commencement of Russia’s

invasion of Ukraine in February this year, but the fertilizer shortages that ensued have also been an

issue for Peruvian agriculture generally, including blueberry farming.

The availability of labor is also a challenge in Peru amidst competition between several agricultural

crops, with many farms in isolated desert areas that either require transportation or the establishment

of lodgings. Protests in late 2020 led to changes to the Law of Agrarian Promotion which imposes a higher

minimum living wage and requires a special bonus paid to workers that is equivalent to 30% of the minimum

wage. Many Peruvian blueberry growers, however, were unaffected by these changes as their worker

remuneration policies and benefits around food and transport already went beyond the minimum requirements

established in the new law.